If you have followed this blog then you might remember that we started project phase 2 on the occasion of spring equinox in March this year. Why phase 2? What was phase 1 and what is phase 2 about? In a nutshell: phase 1 was about developing a non-profit event platform which enables small communities to host activities across 15 different Learning Paths. Phase 1 was about creating a framework for informal learning on sustainable development, which helps different providers of learning experiences to collaborate beyond the limitations of organizations and nations.

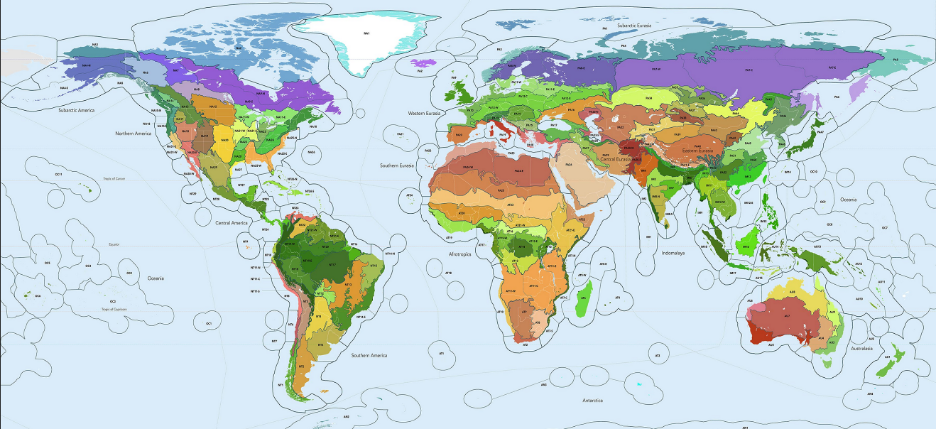

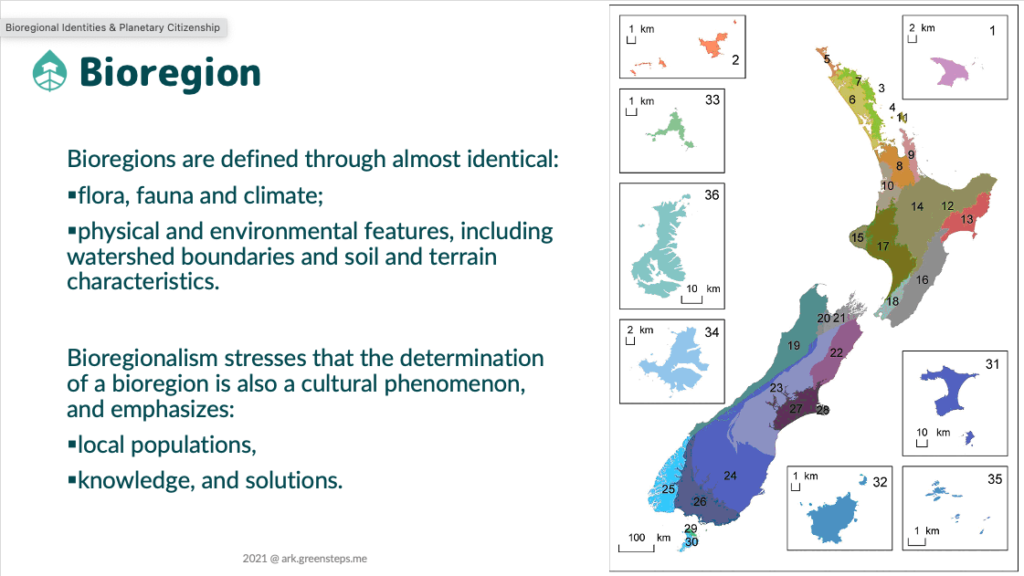

Phase 2 is about a specific dimension of informal learning which creates bioregional identities. Now, that’s probably a completely alien concept to you, but I will try to shed a bit of light on it. We are in an era of tremendous transformation. There is no doubt about this. One such transformation is the globalization we experience through trade and new means of transportation. The human being is today able to cover in a day the distance which took us several weeks only 200 years ago. The same is of course true for all the products which we manufacture.

The acceleration of our lives however becomes even more interesting when we look into how we transmit information. 200 years ago, we used royal postal services to send a message with a coach pulled by a few horses. It would travel – under most favorable conditions – for 10 days between Vienna and Paris or 12 weeks between London and Beijing. Today, we press return and it arrives an instant later in almost any place on Earth. We meanwhile take the existence of the world wide web for granted and are irritated if we don’t get answers from the other side of the moon within 24 hours.

Our perception of the world has completely changed. Technology has propelled us into a single realm of information, but we continue to organize our societies and economies in nation states. Some of us have realized that not only the speed of how information travels changed, but also the space which defines our survival. While we used to live in local ecosystems up until the arrival of the scientific or even industrial revolution, we now are eight billion inhabitants of a single global ecosystem. The recent war between Russia and Ukraine has brought to our attention that central commodities like wheat are shipped around the globe to meet the needs of a growing human population. Rather smallish events like a regional war, are able to threaten the operation of the fragile ecosystem we have created in order to feed ourselves.

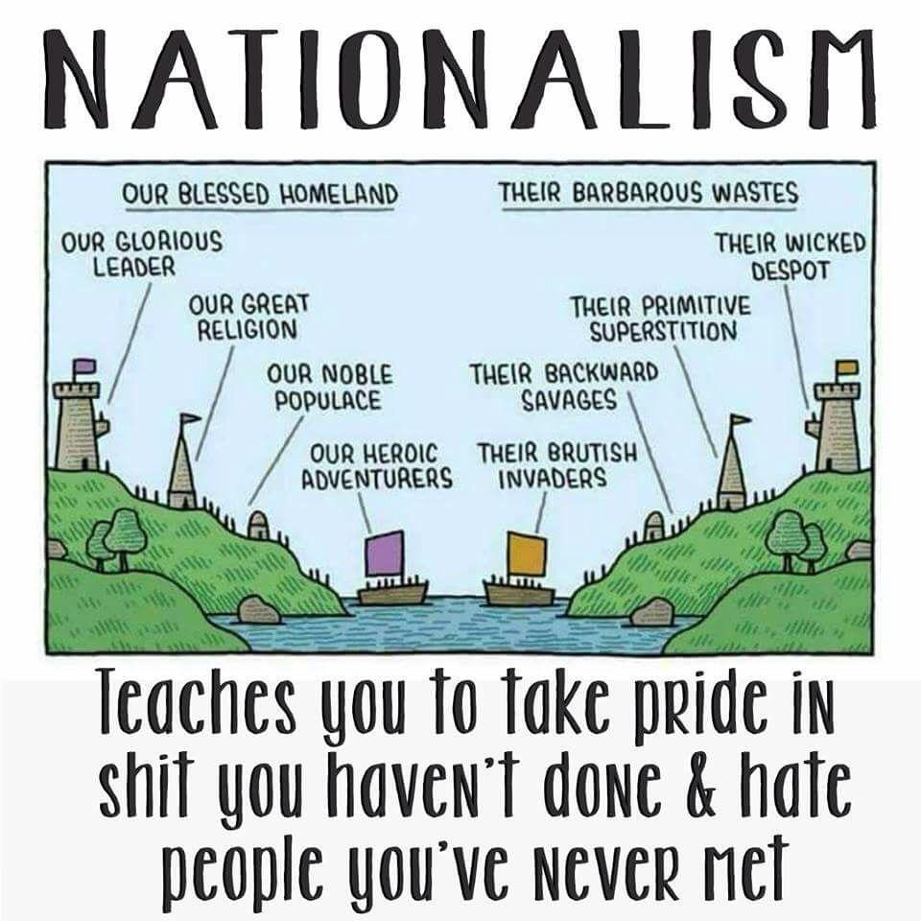

Yet, we continue to think about the world in the obsolete paradigm of nation states, which has been bestowed upon us as a consequence of the industrial revolution. Nation states are per definitionem in competition and this competition has been put into economic terms early on by David Ricardo as the comparative advantage. Instead of humanity producing the commodities which are needed for survival in an agreed manner, nations produce the products in which they have a comparative advantage over others. Ricardo explained not only why countries engage in international trade even when one country’s workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated also that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good.

An economic modelling based on a comparative advantage which did not cause a noticeable tragedy of the commons back in the 18th or 19th century, leads to ecological peril and species extinction if used as behavioral framework for eight billion people. While the comparative advantage is the reality of a free market, we need to accept that the free market does not work well with a finite ecosystem. A paradigm shift is required: a smartly and mindfully regulated market which distributes limited resources in a fair manner. What we experience today, is a depletion of natural resources because humanity has not managed to perceive the planet as a single ecosystem which we need to protect jointly, if we do not want to perish. The tragedy of the commons has transformed in dimension: instead of a local sheep pasture the commons which needs to be safeguarded is the planet at large.

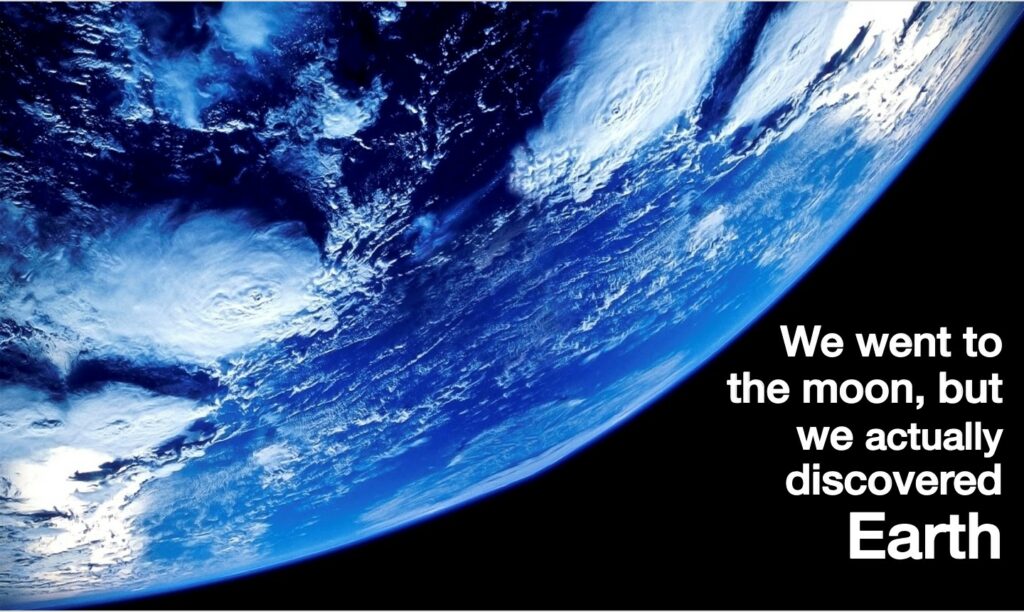

Phase 2 of our project tries to substitute national identities with bioregional identities because they are a stepping stone to the overview effect. Overview effect? another alien concept? Well, not alien but at least extraterrestrial. A team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania examined the testimonies of hundreds of astronauts who had the opportunity to view Earth from space. Their analysis uncovered three common feelings:

1. a greater appreciation for Earth’s beauty;

2. an increased sense of connection to all other living beings;

3. an unexpected, often overwhelming sense of emotion.

Most of the 558 people who have seen earth from space have acquired this overview effect, in particular when they were in outer space, that is beyond the Earth’s orbit. They instantly understood that our planet is a blue pearl protected from an infinite black void by a thin white shield: Earth’s atmosphere. Why do we believe that bioregional identities are of such importance? Because they are a steppingstone to the overview effect, i.e. an emotional transformation which makes individuals empathetic for the planetary situation.

But not only the planetary situation, also our own. The industrial revolution has not only transformed the transportation of goods and information, it has also transformed our sense of self. If we speak today of the Anthropocene, then we rightly do so, because our predator species has impact upon this planetary ecosystem like no other species before us. There is though also another way to look at this term: Anthropocene. For most of our existence we were defined by nature more than by anything else. During the last 200 years political inventions like France, Russia or China have shaped how we think and how we identify ourselves. But these nation-based identities are not only ecologically unsustainable, they are also increasingly unattractive to a growing number of people.

For most of our existence, we did not care much about political borders small and large. We lived in tribes and clans. Our identity was born in the bosom of mother nature and would end in the same place. Anthropologist Gary Snyder writes that human life did always start and end around the firepit. The controlled use of fire which dates back between 1 million and 300 thousand years, did not only set the human being apart from all other creatures, it also gave us a sense of identity which revolves around a location.

This tribal point of reference would remain more or less unchanged for much of human history up to the start of the industrial revolution when firepits were gradually substituted with stoves, central heating and microwaves ovens. Instead of identities which were grounded in nature and intimate tribal relationships, we created identities which were rooted in a constructed culture and increasingly anonymous coexistence. Certain subcultures emerged as a direct or indirect protest against this rise of religious and political empires which destroy communities and aim at the smooth and productive operation of societies. Margaret Thatcher was probably part of such a subculture, most likely of the punk movement, since she is best known for denying the existence of society.

Without doubt there is something primordial about community and even the most conservative human being will feel at times exhausted and frustrated in being part of a society in which we play our roles along the fault lines of an invisible caste system. Real life does not happen in society, it still takes place in tribal circles, no matter where the karmic lottery has dropped your bodily vessel. The co-working empire WeWork has confirmed this perspective by developing a business model around community. Its founder Adam Neumann said that he wanted to re-create the atmosphere of community-based living in a kibbutz, the small Hebrew villages in which he grew up.

Whatever we think about the capitalist attempts of business people to exploit the deep sitting desire of the human being to experience genuine community, we should be able to agree at least since German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies made the lucid distinction between community and society, that it is community which satisfies human needs while society rather creates never-ending cravings. With the onset of the industrial revolution we have begun to experience the Freudian civilization and its discontent in parallel to a drop in child mortality, the end of famine and an extended life expectancy, an increase in unhappiness, depression and all sorts of mental disorders.

The Sane Society as Erich Fromm once wrote, is a sane community embedded in an organizational structure which allows for deep connection with the land. The societies we have seen so far promote the alienation from nature. The communities we need to build in order secure our species’ survival and wellbeing need to be attached to commons as human scale parts in a jigsaw puzzle of bioregions which make up the our planet’s picture at large.

Bioregional Identities are a vehicle for transformation. They give us a new sense of self in an era which demands from us an adaptation to the finite reality of the ecosystems in which we live. Bioregional identities will not abandon the cultures we have created during the last few thousand years, but they will put culture back into its position as being a derivate from nature. Gary Snyder reminds us that its not just enough to “love nature” or to want to “be in harmony with Gaia.” Our relation with the natural world takes place in a place, and it must be grounded in information and experience. “Real people” know their turf. And because they know it, they respect and protect it.

Bioregional identities create a human scale for our connection with the planet. By guiding individuals from the firepit into the commons and from there into the bioregion, they understand that they are part of a superorganism and acquire the overview effect without being shot into the outer atmosphere. Phase 2 of this project offers to its proam users tools to create these human scale territories and connect activity participants with nature. Read more about these tools in our next blog.

Further reading:

- Spring Equinox 2022: ARK Development Phase 2

- Manual video: Bioregions and Overview Effect

- On the Value and the Management of Commons

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Control_of_fire_by_early_humans

- Gary Synder, The Practice of the Wild

- Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontent

- Erich Fromm, The Sane Society

- Ferdinand Tönnies, Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft