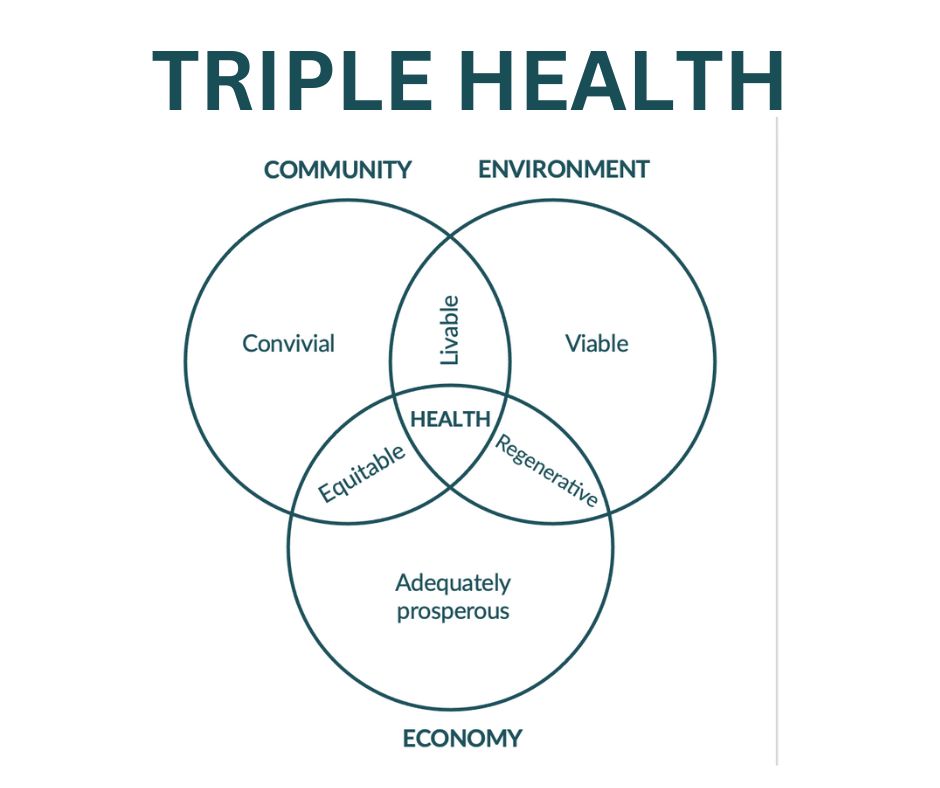

The rise of green movements around the world confirms that environmental awareness and planetary stewardship are the result of economic growth. Collective action against climate change and biodiversity collapse can only be successful when it is tied to fair wealth distribution. A solution to the social crisis is therefore also a solution to the environmental crisis. But, how to make a social & environmental contract work for single societies or even humanity at large?

At the beginning of a new year, I would like to explain once more why I believe that environmental education – phase 2 of this ambitious project – can only succeed if we tie it to a basic universal income – the very essence of phase 3 which we have scheduled to start after Spring Equinox 2023. We are aware that even the importance of environmental education is questioned by many contemporaries, so why bother explaining the economic dimension in this strategy? Only repeated confrontation with the solution to the challenges we are facing as a species, can make them come true. My writing is in this regard both a public prayer and shared plan.

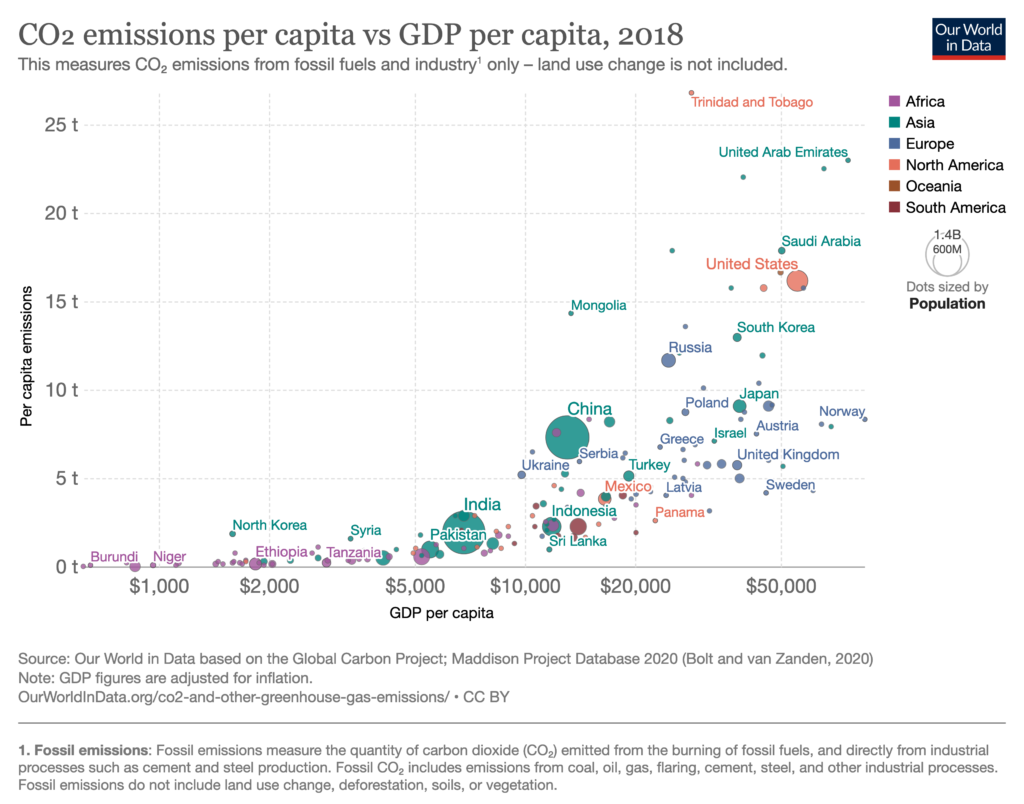

Traveling in a country like Morocco, where I am as I write these lines – confirms first-hand that environmental education can only scale when a certain level of economic development is shared with society at large. Countries that lack even a basic social welfare system are not ready for environmental education, neither their governments nor their people. Their governments either lack the resources to install the required institutions or have not yet noticed their importance. Their people are by wide and large too poor to think about the environment. They think only about themself; they are in a mode of survival, and therefore not to be blamed.

Participating in the foundation of China’s first national park in 2005 and witnessing there the emergence of a green movement in 2013, revealed to me first-hand that a society requires a certain level of economic development in order to produce a number of people large enough to be concerned with the state of nature. It is these well-off people who realize that their own and their children’s survival is being threatened by deteriorating nature. It is only then that they begin to protect the environment and push the government for legal and practical measures. The Economist described in a brilliant 2013 article that the same happened in the 1960 in Japan and the US, and in the 1970s and 80s in Europe.

If economic development in a social and individual dimension is so crucial to manifest environmental concern, we need to deduct that environmental education can only create impact where a certain level of distributed wealth has been obtained. Vice versa, we need to agree that prior to providing environmental education it is required to provide advanced living conditions which give the human being time, space and attitude to take care of the planet.

There is much evidence however that environmental destruction increases with the level of economic development. Inhabitants of rich nations, and within nations the inhabitants of wealthy cities, consume more than inhabitants of poor nations or countrymen with lower income. Increased and above all mindless consumption drives resource depletion and environmental degradation. So, environmental awareness in the widest sense possible must be also the result of something else than acquiring affluence. It seems we have here a sort of chicken and egg problem.

The 50-million-dollar question is about the level of post-industrial economic development required to spread environmental awareness and empathy for the planet. How much personal wealth is needed to care for the planet? Daniel Kahneman pointed in a 2010 TED talk at about USD 60k annual income for Americans, above which material affluence does not create more happiness, below which however deprivation in every aspect of life generates negative impacts. In the words of the noble laureate: Below an income of 60,000 dollars a year, people are unhappy, and they get progressively unhappier the poorer they get. Above that, we get an absolutely flat line. I mean I’ve rarely seen lines so flat. Clearly, what is happening is money does not buy you experiential happiness, but lack of money certainly buys you misery, and we can measure that misery very, very clearly.

If we were to calculate based on that Gallup survey the purchasing power parity annual income that is required in different economies to generate well-being instead of misery, we would not only generate a pretty accurate indicator on how to share global wealth, we would moreover create the conditio-sine-qua-non for environmental education and environmental protection to unfold its potential. Below that basic income, large parts of humanity will be stifled in their potential to develop environmental empathy and will naturally think about survival only. I tried to elaborate on a conditional basic income for the population in and around national parks in Africa as part of a nature protection program which includes humans as integral part of ecosystems back in 2020 and came also then to the conclusion that environmental protection and economic participation go hand in hand. The Spanish film Adu, which is set in three location on the African continent shows with a scary but impactful narrative why wildlife biodiversity protection cannot work without an economic dimension which extends to all inhabitants of such regions.

The deterioration of what we generally call nature is a great albeit frightening opportunity for a leap of consciousness. Global warming, climate change, biodiversity collapse, droughts in one, flooding in other regions might show the rich and wealthy that only in true sharing of affluence, we create the conditions for our species (and others) to flourish spiritually and emotionally, and enter a new phase of evolution of which Karl Marx – if I am not mistaken – spoke of as the end of class struggle and Francis Fukuyama as the end of history. On this subject, it is always recommended to watch Downsizing and ponder on its relevance in connecting the social and environmental crisis

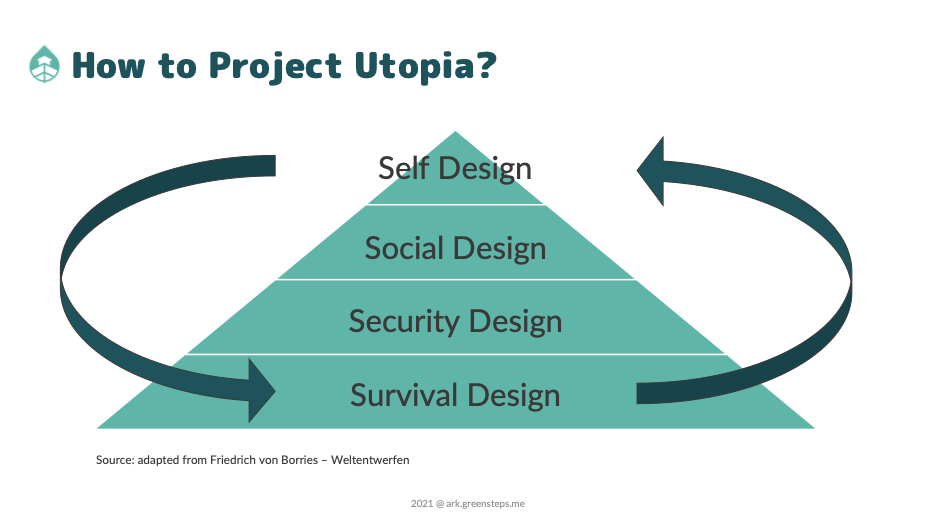

The coalescence of self-design and survival design are the result of such an individual and collective transformation. Humanity shapes itself to survive. It keeps one global book on natural resources available, on humanity’s CO2 footprint, on financial resources generated from human and non-human natural resources, and distributes them in a fair manner, which leaves room to improve one’s lot, but provides a basic safety to follow rules on sustainable living. No more Manchester market pressures to poach ivory, log tropical timber or enter prostitution.

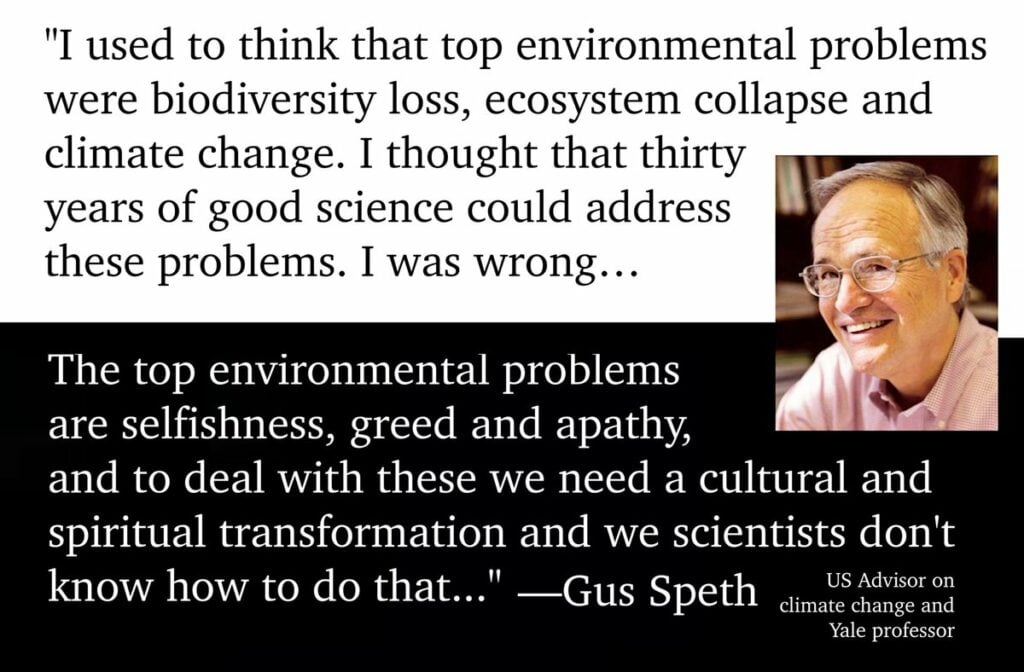

The individual shapes itself in order to make survival of others possible, because it realizes that freedom to exploit diminishes its own likelihood to survive. Education is certainly at the very center of this process but can only happen if supported by a public policy which puts economic security for everybody in the first place. This sounds like utopia, but when we think of the productivity increases which automation has helped us to achieve, it is not so utopian unless we do not believe that we can overcome greed, apathy and ignorance. At one point, nature’s collapse will make even the most self-absorbed turd realize that we are one superorganism which needs to cooperate and share in order to evolve and survive. True sharing of productivity gains generated through automation and digitalization must translate to a universal basic income – and this income can then be tied to environmental learning and sustainable behavior.

The solution to the social crisis is a solution to the environmental crisis.