The future of work was the most discussed topic in Anglo-Saxon media in 2017. Rightly so, because that year people had become increasingly aware of the consequences of artificial intelligence on human work, and not only thought leaders began to ask questions whose answers are not yet, or not easily, forthcoming.

What is the future of work? When will it occur? How do you prepare your children for it? What education does the future of work require?

This article attempts to summarize observations of the last decade and provides answers.

“The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see”

Winston Churchill

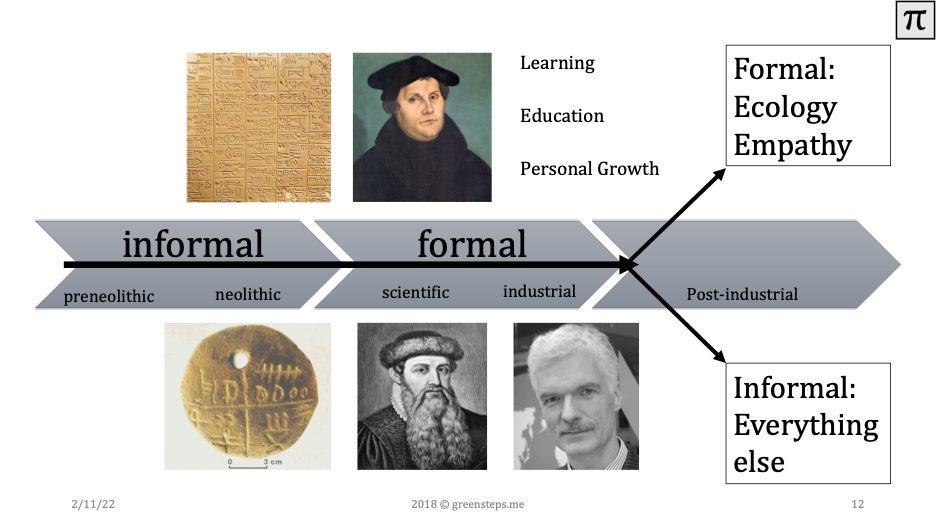

If we want to approach the topic of the future of work, it is necessary to take the so-called longitudinal perspective, because it is common to look only at the present and the recent history. In the longitudinal perspective, we look at a specific topic from its beginning to its imaginable end and thereby gain – loosely based on Winston Churchill – a better understanding of a possible future.

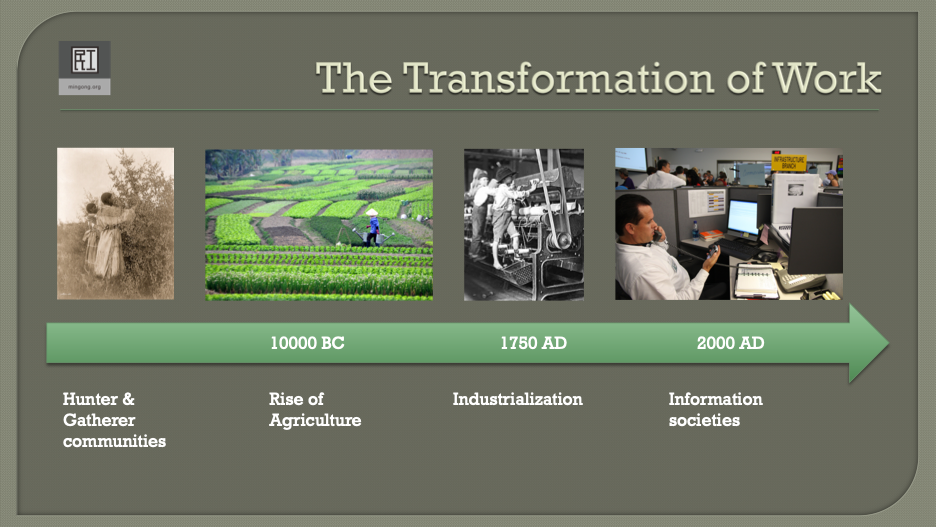

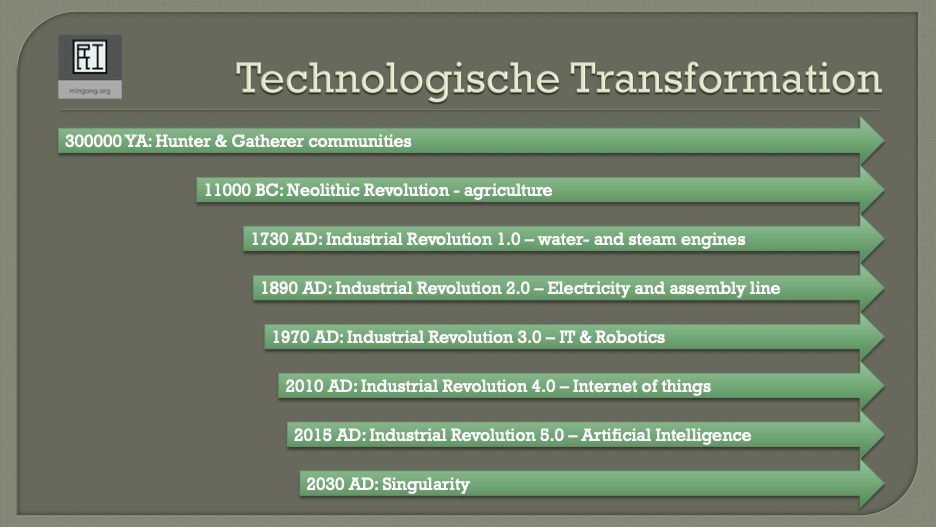

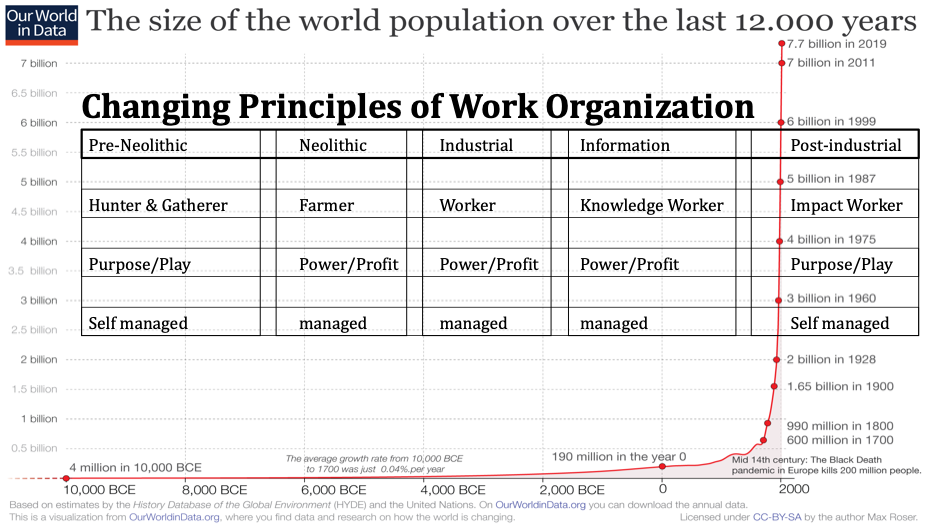

Work is, among other things, a subject of anthropology, which can be roughly divided into four major phases: that of hunting and gathering, that of agriculture triggered by the Neolithic Revolution, and that of mechanical production and electronic information processing, each triggered by the Industrial Revolution. Anthropology gives us an important first insight: homo sapiens has spent by far the largest part of his history as a hunter or gatherer, namely, depending on when one puts the Neolithic Revolution, until about 10,000 years ago. In particular, the changes of the past 250 years are an anomaly that may again be followed by a long period of continuity.

“Work saves a man from three great evils: boredom, vice and need”

Voltaire

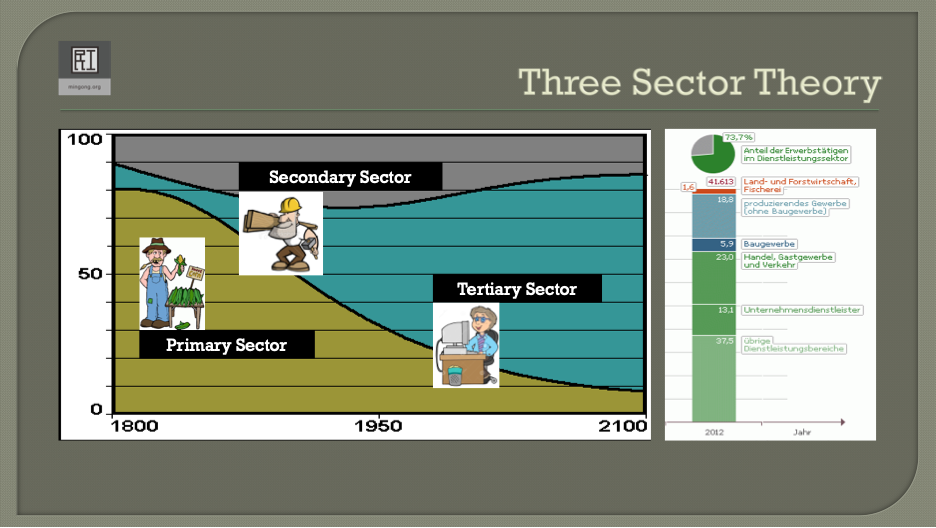

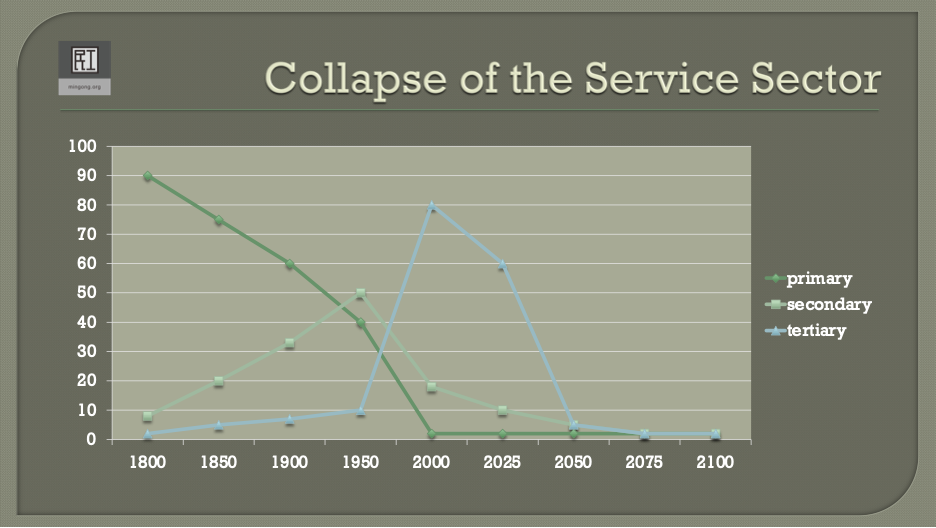

Economists, on the other hand, have given us the commonly known image of the three-sector-hypothesis, which is limited to the last 250 years or so and divides labor into a primary sector of agriculture, a secondary sector of industry, and a tertiary sector of services. The three-sector-hypothesis is a now repeatedly falsified but extremely useful theory from the 1930s that differentiates the national economy into resource extraction, resource processing, and services.

The three-sector-hypothesis has helped to describe a transformation of the labor market caused by technological progress as such: The industrial revolution has increasingly eliminated the need for human labor in agriculture and absorbed this increasingly specialized labor in manufacturing industries. Progressive automation in turn led to the release of labor in industry, which was absorbed predominantly in the service sector. Germany, an economy with an exceptionally strong industrial base, reported the following shares in 2014: primary sector 1.5%, secondary sector 24.6% and tertiary sector 73.9%.

In summary, with regard to the three-sector hypothesis, economists, unlike anthropologists, describe a changing market rather than a human activity. Traditional economists are mainly interested in productivity gains and map them in the context of nation-states. Labor markets are therefore, on the one hand, much larger than the work environments observed by anthropologists, and on the other hand, they are limited to national territories and therefore contradict the globalization of the labor market, which has been significant since the 1990s at the latest.

With paid employment, economists also give us a concept that is very different from the definition of work before the industrial revolution. People participate in an anonymous labor market in order to make a living. Thus, economics bridges to sociology, which gives us a third perspective: that of interpersonal organization. The German sociologist Friedrich Tönnies introduced the differentiation between community and society, and thus demonstrated a central transformation for work as well.

It is commonly assumed that human organizations were small communities until the Neolithic Revolution, and that only agriculture enabled the emergence of societies in the form of principalities, empires, and religions. Societies differ from communities in that they can bind a larger number of people and the larger these groups, the more anonymous they are. In particular, the increase in productivity due to agriculture freed up labor to be devoted to other activities such as specialized crafts (the precursor of today’s industry, science and research), art and culture.

Through this ongoing enlargement of the organizational form, however, one thing above all has occurred: The work concentrated around a community has been alienated from the community and communities increasingly collapsed. If it was unthinkable for man for eternities not to contribute with his work to the survival of a community, with the emergence of society this contribution has significantly moved into the background – and again on a longitudinal perspective: almost abruptly. Covid-19 has revived something of this archaic idea of contribution with the concept of system-relevant occupations, even if it is still related to anonymous societies and thus not easy to understand psychologically.

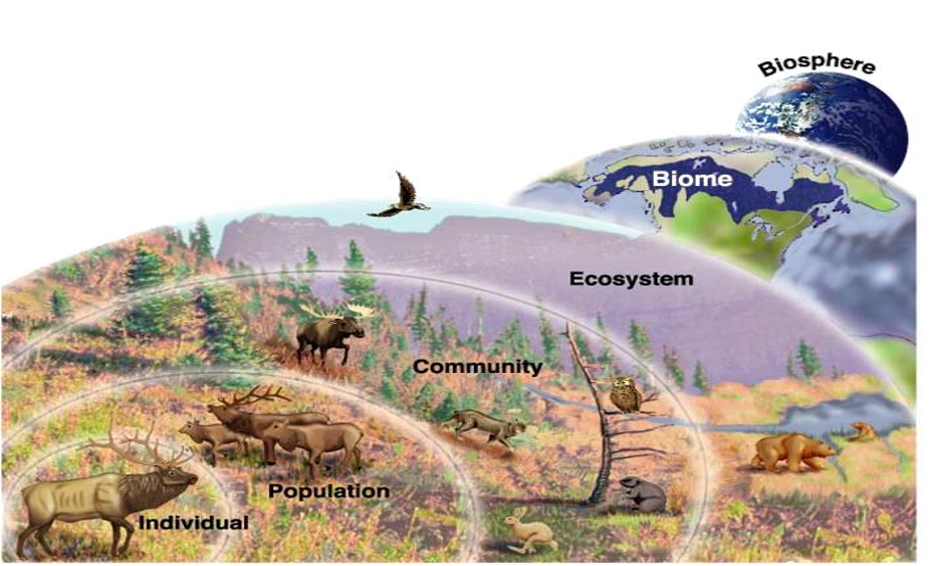

By looking at the contribution made to the survival of a community, a fourth central perspective on the nature of work emerges, which is still not sufficiently emphasized: that of ecology. Work must make sense for oneself, for the community at large, and for the ecosystem as a whole. A look at the professions that are not relevant to the system shows how much work our meaningless societies generate and thus waste not only raw materials but also human resources unnecessarily.

The fact that it is possible in modern societies to have a large number of people engaged in gainful employment that offers no added value for society can be explained by the detachment of the economy from ecology. Whereas in hunter-gatherer communities it was necessary to operate within a limited ecosystem, it is only now, as a result of the climate crisis, that we are slowly becoming aware that a global labor market alienated from the carrying capacity of the earth is just as unsustainable as an economy that does not subordinate itself to ecological framework conditions.

Human employment is in direct competition with automation.

Peter Joseph

The world long thought that politics produces progress, but it is increasingly apparent that technology is the driving force of change in human labor, and that politics only follows technologically induced changes. Technology helps us to a fifth key insight: that the sectors of the labor market described earlier are each transformed and nearly eliminated by different technologies.

In the primary sector, the early industrial revolution through steam power, electricity, and mechanization replaced animal and human labor, so that in a modern economy only 2 percent of the labor force is employed in agriculture. Industry reached its climax in the West during WWII, when it employed as much as 50 percent of the labor force in some economies. Since then, it has been gripped by a mechatronic transformation that has replaced human labor with robots and, most recently, in “smart factories” with the Internet of Things.

The service sector, which was always seen as the salvation from mass unemployment caused by technological progress, has been experiencing miraculous growth since the invention of the computer, silencing all critics who did not persistently look into the technological future. Since the early 2010s, however, there it can’t be denied that the fifth wave of the industrial revolution will destroy the service sector to the same extent that agriculture and industry were previously destroyed.

Artificial intelligence, computers capable of various forms of machine learning, has begun to take over our labor markets. Journalists, radiologists, chess players, Wall Street bankers, up to 70 percent of all known professions will be done better by artificial intelligence than by humans in the coming years, and that’s without factoring in the possible intertwining of AI with robotics. The director of the Zeitgeist Trilogy Peter Joseph has therefore correctly recognized that human employment is basically always in competition with automation as long as it is seen only as paid employment and participation in a labor market.

The future of work is full of dystopian as well as utopian scenarios, some of which have already been painted on the big screen by Hollywood. Wall-E, for example, showed us in 2008 a future of an overweight humanity vegetating on a spaceship and leaving the earth as a garbage dump. In 2009, Surrogates made a world palatable to us in which we do our work and, moreover, every unwanted interaction through avatars and our bodies meanwhile rest apathetically at home.

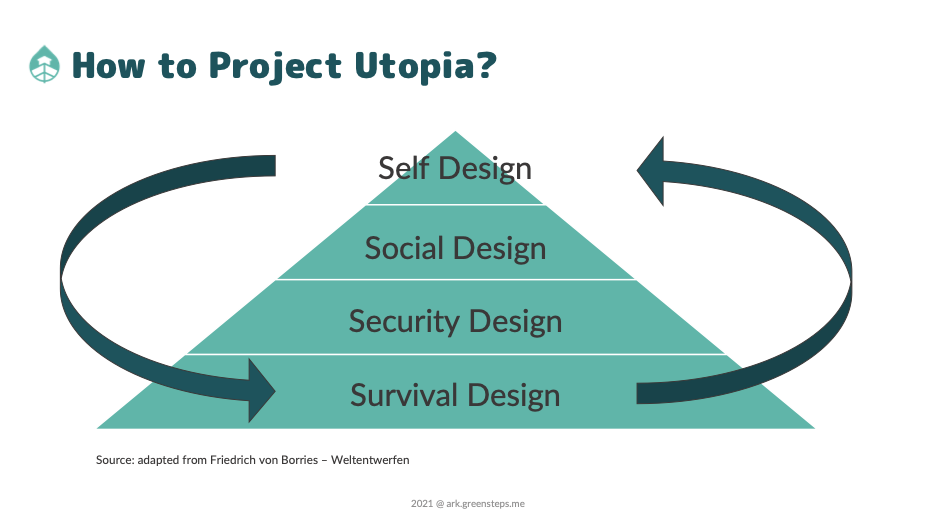

While the imagination of screenwriters knows no bounds, the carrying capacity of the earth as an ecosystem shows us clear limitations and thus provides us with a framework within which we must design a future of work. The designer Friedrich Börries distinguishes between survival, security, social and self-design and declares design to be a political instrument. He believes that each of us has to take responsibility and pursue change by design instead of by disaster. In other words, in the face of the climate crisis, career choice and thus self-design becomes survival design.

Philosopher Thomas Vasek takes a more relaxed view of the question of the right job and assumes, with the spoiled perspective of a Central European, that one may wish for the ideal job. For Vasek, in comparison to Börries, it is less about fulfilling a duty through one’s own work by contributing to the survival of the species and therefore taking up a system-relevant profession, but rather he sees a right to “good work”, which in his opinion should fulfill the following parameters:

- It is in harmony with our values and feelings, so it enables us to live authentically.

- It enables us to have experiences that enrich us.

- It gives us recognition, not just financial recognition.

- It creates reasons for cooperation with other people, i.e. it promotes social bonds.

- It does not permanently overburden us, but it also does not permanently underburden us. It challenges us, so that from time to time we experience a flow, i.e. we become completely absorbed in our activity.

- It also contains freely available time, rest phases, elements of leisure. So it does not consist of just being active all the time.

- It creates habits, giving our lives a reliable framework.

Vasek’s analysis should be enshrined in every constitution, but he overlooks a small detail: life is not about choice for the vast majority of humanity, which, for example, manufactures fast fashion in Bangladesh or Pakistan and thus participates in a global labor market that exploits people and planet. Thomas Vasek focus is the right to good work from a rather European world view, while Friedrich Börries emphasizes the duty to contribute to survival – a perspective which requires the understanding of the planet as a single and fragile ecosystem.

The future of work, if it can and must be designed as Boerries thinks, thus is in a field of tension between ecological and social conditions, which a labor market that assumes paid employment and regards both the planet and humans as a resource to be exploited aggravates even further. The concept of the labor market is a product of capitalism, which needs a fundamental transformation in order to be able to design the future of labor in a meaningful way.

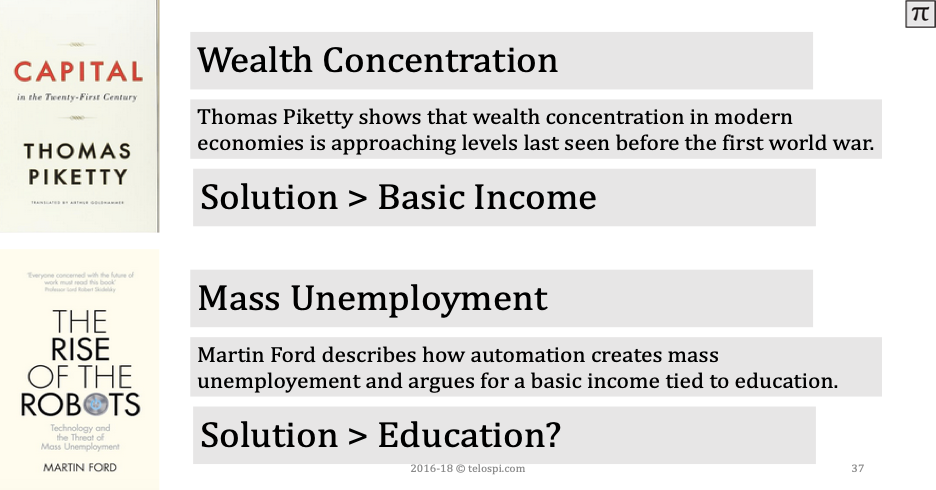

Visionary author Martin Ford has described this tension as a perfect storm, meaning that technological unemployment and environmental impacts develop roughly in parallel, reinforcing and perhaps even exacerbating each other. He sees the greatest challenge of our time in shaping a future that provides broad-based security and prosperity, and believes that understanding education as a public good that must not be influenced by competitive profit or power maximization is the key to finding that path.

In this context, it is worth mentioning the French economist Thomas Piketty, who showed, based on historical data, that the current concentration of wealth is back to where it was before the WWI. He explains that there is only one cause for this, namely that the return on capital is greater than economic growth and therefore, in simplified terms, leads to an increasing inequality of wealth distribution. Thus, Western capitalism, with its immanent rules, steadily extracts wealth from those individuals who can only contribute their labor. It sooner or later must lead to inequalities, which are enlarged by new technologies.

Let us therefore next look at the future of work in this field of tension between ecological and social framework conditions and between social duty and individual right, and ask ourselves what work can absorb the collapsing service sector and how this work is to be remunerated when technology not only destroys paid employment but, in conjunction with the generally applicable capitalist market rules, leads to an increasingly unjust distribution of wealth.

The notion of systemic relevance is undoubtedly associated with duties rather than rights. Systemically relevant occupations are about contributing to the community or society a service without which it would not be possible to ensure its continued existence. However, what activities could provide meaning and fulfillment for people if the production of necessary goods and the provision of services is largely taken over by machines?

When thought of on a large scale, the restoration of our environment, as well as food production close to the consumer, can give many people a meaningful occupation without putting them in competition with machines. This new view of agriculture, where one works to promote one’s own health and preserves or enhances the integrity of one’s habitat, requires a heightened ecological empathy or an overflowing frustration with the generally prevailing office monotony.

Both may have arisen simultaneously in Japan as a result of the affinity for nature that persists in Shintoism as well as one of the world’s highest rates of urbanization, and have found an inspiring expression in the half farmer / half x movement. Originally proposed by Naoki Shiomi in the mid-1990s, the concept is based on the premise that by determining their “X factor,” people can leave behind the 20th century style of mass production, mass consumption, mass transportation, and mass waste disposal while striving for a happier life and a sustainable planet. Not only do rural dwellers embrace this lifestyle, but so do many people who grow food on balconies, rooftops, weekend plots, and in community gardens.

Shiomi recommends setting the bar as low as possible for people to start farming: People should do what they can, whether it’s balcony gardening or rooftop gardening, in places they love. If you set loose rules, like 30 or 40 minutes a day to work with the soil and plants, it becomes easier for more people to start farming. I think a lot of people feel that getting into farming is too much of a challenge.

The half farmer / half x concept also helps us to take the thoughts of Friedrich Börries and Thomas Vasek to the next level, because there is no doubt that food or the contribution to food production is a contribution to survival and thus meaningful fulfillment of duty, which has the pleasant side effect in times of climate change that unnecessary greenhouse gases are avoided by the transport of food. The half x component reflects the right to occupy oneself with those things that perhaps serve self-fulfillment rather than fulfill a contribution to the community. In as such, Börries’ and Vasek’s ideas are aligned and define a future of work which has different dimensions and is most likely different from a 8-5 job.

Applied to the three-sector hypothesis, the half farmer/half x concept means that more people are again participating in the primary sector and thus in the extraction of raw materials. They no longer do this in paid employment, but rather in the form of a leisure activity and similar to flexitarians in freely chosen intensity, but through this time they not only receive food and an added health value, but also a direct confrontation with the ecological situation of our planet and thereby consciously or unconsciously increase their understanding of systemic changes such as climate change.

If half farmer / half x represents a future of work that is viable for many and in harmony with the carrying capacity of our planet, then the only question that remains to be answered is how the basic income required for this must be structured. Because one thing is certain, at least in an agriculture flooded by EU subsidies: the average citizen will not be able to earn his living with balcony gardeners, which gives him the opportunity to dedicate part of his time to x.

Martin Ford argues that a basic income should not be unconditional, but should imply certain obligations, especially those related to education. He shows that an unconditional basic income is a perverse incentive that leads to dropping out of education and thus deprives young people in particular of the motivation to strive for constant self-improvement. Basic income is thus not only the fulfillment of the social contract dreamed of by Rousseau, but also potentially a danger of turning well-fed but meaningless individuals into the emblem of postmodernism.

Learning therefore has an enormously important place in the discussion of the future of work, one that has received little interest to date. Indeed, learning will take up a large part of the duty that every citizen has to fulfill as a contribution to community and society. This leads however to a paradigm shift of a dimension not to be underestimated, which Martin Ford has already indicated: Education must not only be seen as a public good, but system-relevant education is – probably never ending – work of the individual for which he has to be paid.

We repeat the assumption that in a few years 70% or more of the jobs known today will be done better by machines or algorithms than humans can do and that only a few areas of today’s labor market such as education and health will be spared from automation because machines cannot replace interpersonal contacts. We repeat the assumption that it is nevertheless more productive to replace humans with machines and that only a few workers will be paid because they still contribute to the productivity of an economy in a measurable way. What is to be learned under these changed conditions?

Philosopher Konrad Paul Liessmann discusses how the classical educational canon of the 19th century, i.e. the study of Greek, Latin, Schiller and Goethe, could be replaced by a normative European educational canon of the 21st century. His thoughts are extremely worthwhile reading – because educated – but they perpetuate the division of society into educated and uneducated and completely omit an economic and thus social, as well as ecological and thus sustainable dimension. Furthermore, the memory of a European educational canon is not sufficient in a global world. It is time to discuss a global educational canon.

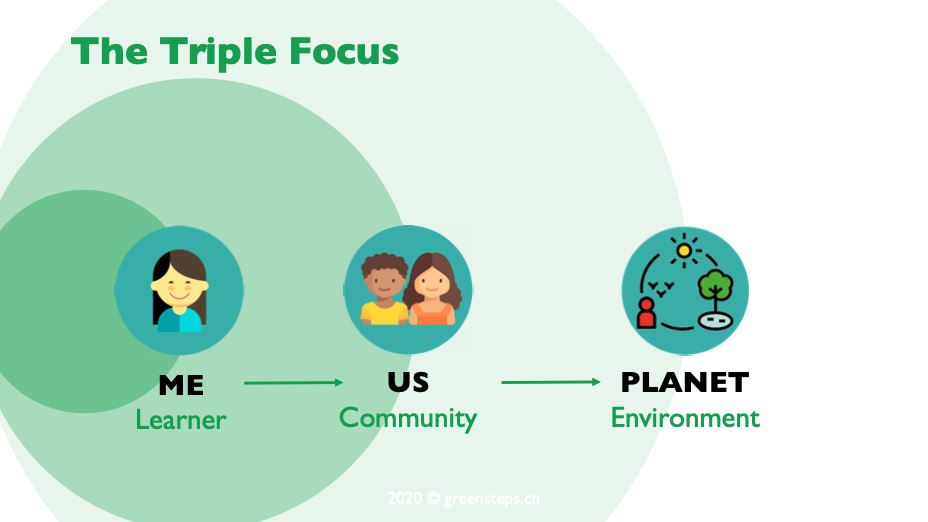

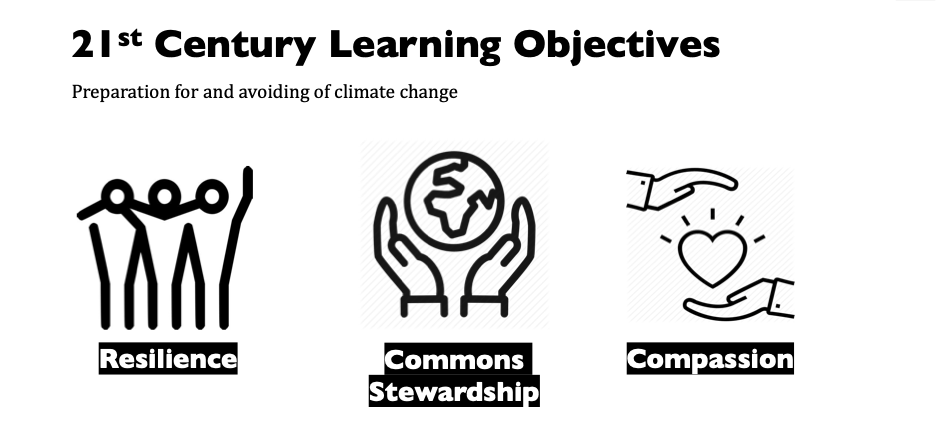

Education must be a public good that minimizes social differences or at least creates a starting point for eight billion people, regardless of their social or ethnic background, to make a living without conflict with the limited resources of a finite world. The future of work is therefore a learning that can be well described with the Triple Focus: the focus on and understanding of one’s own emotional inner life, the focus on and understanding of interpersonal relationships and the focus on and understanding of ecological relationships.

The ecological and social framework of the Anthropocene therefore dictates that we no longer speak of a labor market, but rather of a world of work in which we have recognized that the compulsory learning content of the industrial age is obsolete and what was once considered complementary has become compulsory: empathy for oneself, others, and the planet constitute a new global educational canon, while the STEM-heavy content of our current curricula are complementary subjects – for which no basic income should be paid.

By making education about emotional resilience, empathy, and neighborhood responsibility compulsory, we are not only preparing children and youth for the challenges of climate change, but also initiating a paradigm shift that is once again changing the nature of work. Management philosopher Peter Drucker has described just such a change in work as an event that may transform civilization like no other, which is undoubtedly exactly what we need right now.

Very few events have as much impact on civilization as a change in the basic principles of organizing work.

Peter F. Druckler

A renewed and final look at the longitudinal perspective shows us a non-obvious connection between demographic development and the principles around which mankind has organized work. A highly simplified attempt to classify the changes shows that since the Neolithic Revolution, work has become increasingly organized by an orientation towards power and profit, and as a result, more and more people have lost the joy in their work.

The ecological turning point that we have undoubtedly reached could herald a post-industrial understanding of work, which on the one hand is again more self-organized, but on the other hand takes the worker into responsibility and asks him to organize his work according to social and ecological impact. As Mahatma Gandhi once said, our planet offers enough to satisfy the needs of every human being, but not their greed.

The change from hunter-gatherer, to farmer, to worker, to information worker, could therefore really result in a “half famer / half x impact worker”: a person who, within a healthy economic framework, must ask himself where he can meaningfully contribute to strengthen the local community and the global ecosystem. This change will be a long-term one, as indicated at the beginning, marking a new stage of cultural evolution in which work may once again be understood as a playful vocation – not only by a happy few but by the majority of mankind.

References:

- Andrew McAfee, What will future jobs look like?

- David Richard Precht – Jäger, Hirten, Kritiker: Eine Utopie für eine digitale Gesellschaft

- Friedrich Börries, Weltentwerfen – Eine politische Designtheorie

- Thomas Vasek, Work-Life-Balance Bullshit: Warum die Trennung von Arbeit und Leben in die Irre führt

- Martin Ford, Rise of Robots – Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future

- Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century

- Japan’s Growing Trend: Part Time Farmers

- Interview with half farmer / half x founder Naoki Shiomi on Insitute of Studies in Happiness, Economics and Society website

- A New Key Phrase for a New Age: half farmer / half x.

- Andy Couturier, The Abundance of Less

- Konrad Paul Liessmann, Bildung als Provokation

- Daniel Goleman, Peter Senge, The Triple Focus – A New Approach to Education

- Peter F. Drucker, The Essential Drucker